The mix (and mess) of Packet Filter Linux - Part 1

Overview

Introduction

So you’ve got a brand new Linux distribution. You start your Kubernetes distributions, and decide for a specific CNI that provides network policies.

Then you figure out that something is (or is not) working, does an iptables -L to check what is going on and boom: where are all my iptables rules? Worst of all, you put some newer rules but they seem not to work and your traffic is still being blocked.

Well, welcome to modern Linux. IPTables is not anymore the only way of doing packet filtering (since a long time, to be honest) and there might be something else blocking it.

The idea of this article is to show some of those packet filtering technologies, with simple examples and what’s their position during the packet filtering inside the flow.

Spoiler alert: I’m not really an IPTables/nftables/eBPF specialist (far from that), and the idea here is to study the impact of each one. Feedbacks of this study are more than welcome!

A little bit of history

Back in time (before I’ve ever started to work with Linux), kernel 2.2 did already have capabilities of packet filtering with ipchains

In 1998 it was superseded by iptables which has been the de-facto command to make packet filtering in Linux since then.

And why do I say “command”? Well, Linux is only a kernel composed of features. The packet filtering is done inside the kernel, once the packet arrives in the network card and until it leaves the host. Iptables is the command, in userspace that knows how to say to the kernel “insert this rule that will DROP all the icmp packets”, as an example.

The same happens in almost everything in Linux. When you issue the “ls” command, ls is a program inside the userspace that will make a syscall to Linux Kernel, that will then ask for the filesystem which files it have (which turns into another call to the disk, listing it contents).

So from now one, when we say “iptables” and “nftables”, remember that all of them are just a layer/commands that call the kernel API and put rules into that for the proper packet filtering. By the way, the part of the kernel that deals with packet filtering for both of those programs is called “netfilter” but each one have its special part in the netfilter subsystem.

I’ll not enter into eBPF behavior right now, as it’s a program that is compiled and runs inside the kernel (not a userspace command). We’ll see more about that in the Part 2 of the article

Well, going back to history: after iptables, in 2014 nftables got merged into the kernel. Now the thing here is that, nftables also uses netfilter, but in a different part of the kernel. So you might have iptables and nftables co-existing, but one does not know about the existence of the other.

Yes, it happens. A packet might arrive in the nftables part of the netfilter, but never arrive in the iptables part. And we will see that happening in detail.

In parallel with nftables, a new technology called eBPF was rising in the kernel. But the main idea of eBPF wasn’t to be packet filtering (although the name is Extended Berkeley Packet Filtering) but allow programs to be compiled and attached to the kernel to provide observability, networking and other features.

Methodology

So for this study, the methodology is going to be quite simple. I’ll install a Linux distribution with Kernel >= 5.4, and make the following tests:

- Run a simple tcp port 12345 with netcat to verify the port is open:

nc -l -k 12345 - Create rules to log and drop a packet to TCP port 12345 in each of the netfilter stacks and check the logs to see where is it being dropped.

- Change the rules to accept the packet in each of the netfilter stacks, and check what’s the way the packet flows through the logs.

- Make some experiments / inversions both in input and output chains to gather more information about the positioning of each stacks

- Put some eBPF + XDP (in part 2) and check if the package arrives at the netfilter stack

- Make the same test, but now putting eBPF + TC program (again, in part 2)

- Try to join all of this with OVS and check what’s the position of OVS in the above mess :)

I’m not entering into the packet forwarding flow (the machine acting as a router) in this article, but this can be explored further later (maybe a Part 3?)

IPTables

So now, let’s go through IPTables with some brief explanation.

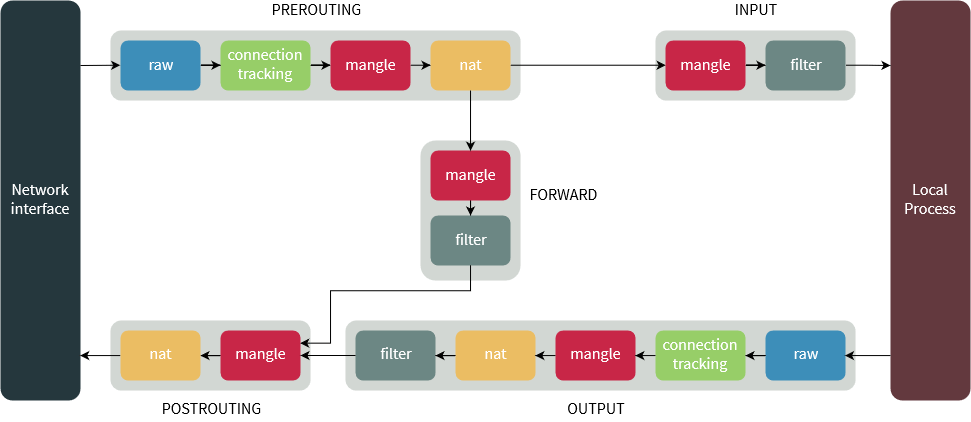

IPTables as the name says is composed by…tables! Tadah! So, basically you have 4 tables here:

- Filter -> deals with packet filtering inside the machine. We’re going to use this one in this article

- Nat -> Deals with packets being routed through the machine.

- Mangle -> Deals with packet behavior changing

- Raw -> this is a special one. Raw table deals with packets before the kernel starts tracking it (see conntrack).

The below picture shows the packet flowing through iptables:

So, to get started let’s create the simpler log and drop iptables rule. I’ll use the command iptables-legacy to use the old iptables, as the actual “iptables” command points to iptables-nft which inserts the rule into nftables:

1iptables-legacy -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 12345 -j LOG --log-level 4 --log-prefix ipt-input

2iptables-legacy -A INPUT -p tcp --dport 12345 -j DROP

3iptables-legacy -A OUTPUT -p tcp --sport 12345 -j LOG --log-level 4 --log-prefix ipt-output

With the code above, the linux kernel will log, with a level of “Warning” when a packet arrives in tcp port 12345 and drop it. Also when it leaves the machine with source port 12345 it will be logged (for further tests). Assuming the port 12345 is up and listening connections, and the above filter rules has been already created, let’s see what happens in the log. I’m wrapping the log here to fit in the code snippet ;)

1Sep 13 20:34:53 fw123 kernel: [ 719.092757] ipt-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

So the packet arrives into the stack and gots logged. After that, the packet is dropped by the DROP rule.

Adding NFTables to the recipe

As IPTables, NFtables also works with tables. But differently from IPTables, nftables was designed so the chain of rules is much more simpler, so when you got a rule that needs to “log and then drop” the rule is evaluated as once, instead of going through the whole stack. Also iptables deals natively with “ipset”, which allows you to create rules with sets that can be updated dynamically, instead of having the need to change directly a rule (delete a rule, create a newer rule).

There are some other features that I’m not going to jump in here, but it’s worth reading nftables wiki: https://wiki.nftables.org/wiki-nftables/index.php/Main_Page and there’s a nice nftables reference and comparison here: https://www.slideshare.net/azilian/nftables-the-evolution-of-linux-firewall

So to create nftables rules, we can go through two different ways: using the nft command, that deals natively with the nftables netfilter stack, or using the iptables-nft command, that brings compatibility with iptables command syntax.

For this test I’ll use the native command and load the following rules:

1flush ruleset

2

3table inet filter {

4 chain input {

5 type filter hook input priority 0;

6 tcp dport 12345 log level warn prefix "nft-input" accept

7 }

8 chain forward {

9 type filter hook forward priority 0;

10 }

11 chain output {

12 type filter hook output priority 0;

13 tcp sport 12345 log level warn prefix "nft-output" accept

14 }

15}

So the rules above will log and accept the package. This way, we can see if it flows first into iptables or nftables. If iptables is in the front, the package will be dropped without any log from nftables. They can be loaded with nft -f file-containing-rules

So our scenario now is:

- nftables input -> accept

- iptables input -> drop

And here it is. By the log below, we can see it entering nftables and then iptables. Again, the logs are wrapped to fit into the code snippet:

1Sep 13 21:14:26 fw123 kernel: [ 3092.194827] nft-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

2Sep 13 21:14:26 fw123 kernel: [ 3092.194869] ipt-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

Let’s change the input scenario to the following:

- nftables input -> drop

- iptables input -> drop

1Sep 13 21:16:38 fw123 kernel: [ 3224.260511] nft-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

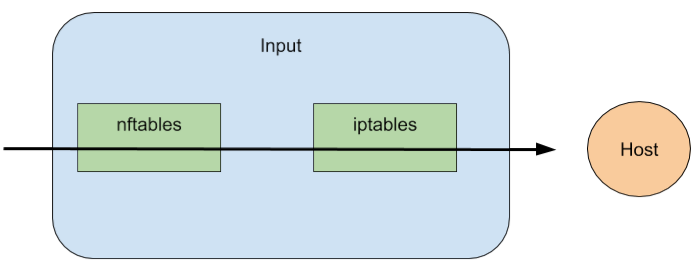

No further iptables log appears!. This means that, regarding the iptables and nftables input flow, we can say that nftables has precedence over iptables as the following diagram:

So let’s move to the output scenario. What I want to check is: who is the last mile when a packet is leaving the host? IPTables or NFTables?

So remember that iptables rules were created to accept the output? So we can change the input rules of both nftables and iptables to log/accept, and then start working in the output rules:

- iptables output -> log/drop

- nftables output -> log/accept

1Sep 13 21:27:12 fw123 kernel: [ 3858.172623] nft-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

2Sep 13 21:27:12 fw123 kernel: [ 3858.172684] ipt-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

3Sep 13 21:27:12 fw123 kernel: [ 3858.172736] nft-output IN= OUT=ens33 SRC=192.168.86.128 [...]

4Sep 13 21:27:12 fw123 kernel: [ 3858.172750] ipt-output IN= OUT=ens33 SRC=192.168.86.128 [...]

So what we can see here is that the packet enters into nftables, then goes to iptables, goes back to nftables and then reaches iptables.

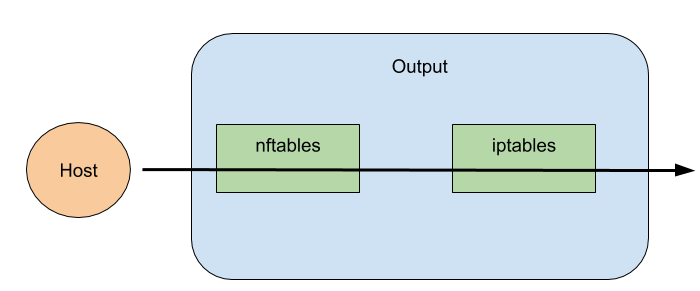

Can we surely say that iptables is the last mile of the packet processing? Let’s change the rules to:

- iptables output -> accept

- nftables output -> drop

1Sep 13 21:30:27 fw123 kernel: [ 4052.554977] nft-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

2Sep 13 21:30:27 fw123 kernel: [ 4052.555079] ipt-input IN=ens33 OUT= MAC=00:0c:29 [...]

3Sep 13 21:30:27 fw123 kernel: [ 4052.555137] nft-output IN= OUT=ens33 SRC=192.168.86.128 [...]

So here it is. The packet never reaches the output log rule from iptables. So we can surely say that the following represents a diagram of the packet flowing to outside of the host:

Conclusion (so far)

So you got something strange in your environment and don’t know why some traffic is being blocked even if no iptables rule is doing that. As we’ve seen here, nftables rules have precedence over iptables rules.

If they were created with the compatibility command line tool (iptables-nft) you should first take a look into the output of both commands: iptables-legacy -L and iptables-nft -L and try to understand if there are rules in both places, what is inserting those rules there and why.

Kubernetes, as an example, has a nice wrapper called.. iptables-wrapper and helps the components that use iptables to decide which one should be used: the legacy one or the compatible one. But remember, as Kubernetes is not aware of how the other parts of the system (aka CNIs) insert the rules, you might have something messing up with things :)

In the next part of this article I’ll take a look into eBPF and the multiple ways of packet filtering. And also, how they deal with netfilter stack.