The mix (and mess) of Packet Filter in Linux Part 2 - eBPF + XDP

Overview

Introduction

In the first part of this article, I’ve shown the most common (so far) methods of doing packet filtering in Linux.

This part of the article is all dedicated to cover a brief introduction of eBPF and XDP, being used to packet filtering. I’ll not cover the usage of eBPF to monitor resources and performance, but there’s plenty of materials available and I’ll put some at the end of this article.

Spoiler alert: As I’ve said in the previous article, I’m not a expert of eBPF, but a new learner. So expect mistakes, and provide me feedback! I do appreciate that!

What is eBPF

The simplest definition I’ve seen somewhere is that eBPF is a way to run specific and confined programs within Linux Kernel, but without having to put code into the Kernel tree or developing modules.

Some articles define eBPF as a “Virtual Machine” (in the concept of isolation, not the VMs like KVM thing) that run programs triggered by some Kernel action.

As an example, imagine a system call that happens (like opening a file) and you want to trigger an action to count how many times that system call happens. Or a program that is triggered when a packet arrives on a specific network interface.

Because those programs are written in C (yeah, sorry!), compiled and attached to some part of your system, eBPF needs to count with some user space area to read and write dynamic data. This area is called map, and can be manipulated while the eBPF program runs.

So, for our examples, we’re going to write a really simple packet filter program, attach it to our network interface and see what and how it happens.

For some more detailed explanation of eBPF, I recommend the following readings:

Methodology

The methodology is going to be pretty much the same as the previous part of the article: write a program that logs and accept (or drop) a packet in port 12345, open a netcat listening in this port and trigger the actions.

So for the sake of this article, the action that is going to trigger our program is a packet arriving on the network interface, and the magic is going to happen there.

eBPF have at least two ways to deal with the packet filtering, like XDP, that I’m going to cover them now, and TC that I’ll cover in some other article

XDP

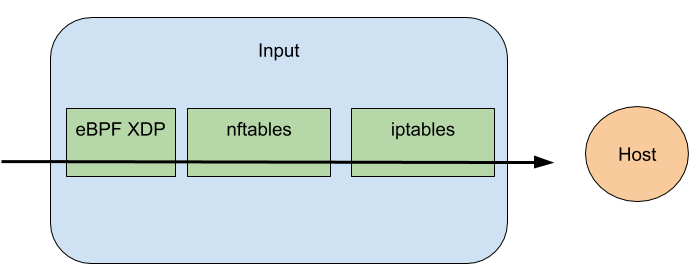

XDP, also known as eXpress Data Path is a specific eBPF program that runs close to the Network device. It’s run even before the packet can arrive at the kernel stack.

There are some network devices that support executing XDP programs directly, so yes, XDP is so powerful that you can process and take an action (like drop) a packet almost in the wire, without needing to overload your kernel.

Because such a low level processing is executed, we need to first have some understanding of how a network packet is composed, so let’s assume this is an Ethernet packet.

Nice, so we’re mostly interested in the IP part (the source and destination address) and TCP part (Dst port 12345).

Hopefully there are some helper libraries that allow us to extract the part we’re interested in. I’ll not go through the situation “if this was an IPv6 IP packet”, but the program may be different.

I’m using this nice article as a reference to write my program, but will use a TCP packet instead of an UDP one.

So, to start this, we need to have clear that this is a program being run almost in the wire, so we’re receiving bytes. Those bytes are represented by XDP with a struct called xdp_md and contains all the necessary data encoded. In this struct you can see fields as data (that represents the start of the packet), data_end (that represents the end of the packet) and fields that represents which was the device that the packet arrive and leaves the machine (ingress_ifindex and egress_ifindex).

But as far as I know and some folks have stated to me, XDP only works with ingressing packets, so you cannot take an action in a packet leaving the machine, other than changing it’s attributes, like the destination IP.

Based on the OSI Model we will need to dissect the layer 2 (ethernet), shift to the layer 3 (the IP protocol) and then to the layer 4 (the TCP part) to get our information, so we’re going to code something like this to get our information:

1int myxdpprog(struct xdp_md *ctx) { // Receiving the bytes in the pointer "ctx"

2 void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data;

3 void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end;

4 struct ethhdr *eth = data;

5

6 if ((void*)eth + sizeof(*eth) <= data_end) { // Assuming this is an Ethernet Frame

7 struct iphdr *ip = data + sizeof(*eth); // Populating the IP part

8

9 if ((void*)ip + sizeof(*ip) <= data_end) {

10

11 if (ip->protocol == IPPROTO_TCP) {

12 struct tcphdr *tcp = (void*)ip + sizeof(*ip); // And then the TCP part

13 [...]

OK, great. So this is a bunch of uncontextualized C code, what does this mean? Exactly what is stated before: we receive the bytes, and dissect them all over as a IPv4 packet with TCP protocol.

Now that we have:

- An

ipvariable containing a iphdr struct that contains fields like source (saddr) and destination (daddr) IPv4 address - A

tcpvariable containing a tcphdr with fields like the source (source) and destination (dest) port.

Putting all this together we will have a “simple” program like this:

1#include <linux/bpf.h>

2#include <linux/if_ether.h>

3#include <linux/ip.h>

4#include <linux/tcp.h>

5#include <netinet/in.h>

6#include <bpf_helpers.h>

7

8#define bpf_printk(fmt, ...) \

9({ \

10 char ____fmt[] = fmt; \

11 bpf_trace_printk(____fmt, sizeof(____fmt), \

12 ##__VA_ARGS__); \

13})

14

15SEC("xdpprogram")

16int myxdpprogram(struct xdp_md *ctx) {

17 void *data = (void *)(long)ctx->data;

18 void *data_end = (void *)(long)ctx->data_end;

19 // Dissecting the Ethernet Frame

20 struct ethhdr *eth = data;

21

22 // Does the size of the packet really fits as an Ethernet Frame

23 if ((void*)eth + sizeof(*eth) <= data_end) {

24

25 // Dissecting the IPv4 part

26 struct iphdr *ip = data + sizeof(*eth);

27 if ((void*)ip + sizeof(*ip) <= data_end) {

28 if (ip->protocol == IPPROTO_TCP) {

29

30 // Dissecting the TCP part of the program

31 struct tcphdr *tcp = (void*)ip + sizeof(*ip);

32 if ((void*)tcp + sizeof(*tcp) <= data_end) {

33

34 // And now we can see if this is port 12345 :)

35 if (tcp->dest == ntohs(12345)) {

36 bpf_printk("XDP drop on TCP port 12345\n");

37 return XDP_DROP;

38 }

39 }

40 }

41 }

42 }

43 // Take a default action

44 return XDP_PASS;

45}

46

47char _license[] SEC("license") = "GPL";

Wow wait! What is this all about?

OK, so first of all, eBPF programs should ALWAYS return from the function, otherwise they won’t compile. XDP programs have some actions that can be taken:

XDP_DROP- Drops the packetXDP_PASS- Pass the packetXDP_TX- Returns the packet to the interface that received itXDP_REDIRECT- Redirect the packet to another interfaceXDP_ABORTED- An error in the application happened, and the packet is also dropped.

Also, remember the code runs as a Kernel program? This way, we cannot simply log with a printf call. Instead we need to log as a kernel program and this is what the call of bpf_printk does. This is a macro defined in the top of the file, and which calls bpf_trace_printk that is provided by the header “<bpf_helpers.h>” which is part of libbpf and will be shown further.

The SEC directive is a macro that defines the program name that the “ip command” (you’ll see it later) looks to load into the device. You can have multiple programs in the same source code, this way you need to name them.

Also, we need to convert the integer “12345” to something that represents the port in the packet, so the function ntohs is used. This is provided by the header “netinet/in.h”.

Finally, because we’re using the helpers functions, the license of the program MUST BE GPL, so the last line defines that.

Compiling and loading everything

OK, so we have our program. How can we use it? It needs to be compiled with and loaded in the device that is going to deal with the packets.

There’s a bunch of ways of doing this, I’ll try to keep it simple.

First of all, you need to install all the necessary tools to compile the program. You can find the dependencies for a good number of distros here. In my case, I’m using an Ubuntu Server for the tests so:

1sudo apt install clang llvm libelf-dev libpcap-dev gcc-multilib build-essential linux-tools-common linux-tools-generic

Also you’ll need to download libbpf:

1git clone https://github.com/libbpf/libbpf.git

Now, to compile the program, considering it’s source is called drop12345.c, simple do:

1clang -Ilibbpf/src -O2 -target bpf -c drop12345.c -o drop12345.o

NOTE: Please be aware, I don’t know if this is the safer way to compile the program, as this is an EXAMPLE!!

NOTE2: If you have errors compiling, make sure the -I argument is pointing to the libbpf/src directory, and also that you’re using the right libraries in the “include” directives on the C code. Also that you have all the linux kernel headers file installed :)

And voilà! You have an object called “drop12345.o” that can be loaded in your network device.

So let’s do it (remember to replace ens33 with the name of your device)

1ip link set dev ens33 xdp obj drop12345.o sec xdpprogram

Now you can try to connect to the port 12345 of your host, and see the logs with:

1sudo cat /sys/kernel/debug/tracing/trace_pipe

2 <idle>-0 [001] ..s. 6541.153908: 0: XDP drop on TCP port 12345

3[...]

If you need to unload the program, simple do:

1ip link set dev ens33 xdp off

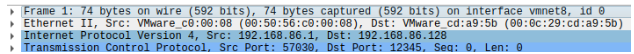

And where is XDP positioned?

So remember when I said earlier that the XDP programs are executed before the packet can have a chance to reach the rest of kernel stack?

In the previous article, we’ve seen that nftables is positioned before iptables when dealing with filtering, so let’s load our previous nftables ruleset, and see if the packet is logged by XDP or by nftables:

Before loading the XDP program, we can see by the timestamp that nftables is dropping the packet:

1[ 6976.808976] nft-inputIN=ens33 SRC=192.168.86.1 DST=192.168.86.128 DPT=12345

But then, when the xdp program is loaded, no further log appears in nftables stack, but take a look at the timestamp of the following message:

17237.743455: 0: XDP drop on TCP port 12345

To confirm:

I’m not going to make the Output test, as it’s stated that XDP is only for incoming packets. But I can try to take further tests in some later article :)

Final Thoughts and next steps

Right now the program is simple and static, so if you need to dynamic update it you need to change the code and recompile it. eBPF can use a structure called map, which can be used to “trade” informations between the running program and userspace, as an example dinamically feeding a program with IPs that should be blocked.

In my opinion, the biggest issue when using eBPF is to know exactly what is being executed, as this is a static compiled program. One can compile and attach it to a network interface and if you don’t have the source code, you won’t know what is happening, while with IPTables and NFTables you can simply dump the rules.

A tool called bpftool can be used to show you things like “What program is loaded in which part of the system”, like XDP or TC (that will be covered in the next post), but still, you only know where, but not what. There was an effort to create a program called “bpfilter”, but it seems to be frozen right now.

Finally, XDP is not the only way that you can use eBPF programs to make packet filtering in Linux and in the next article I will cover how eBPF + TC programs works :)

Thank you for reading this, I expect to clarify a little bit this new world (also for me!) of eBPF stuff :)

And thanks for all the hard work the community has been doing making eBPF a great new technology, and also documenting! The next section have some nice references that I’ve used, but there’s a lot more materials, posts, etc.

References:

- https://ebpf.io

- https://prototype-kernel.readthedocs.io/en/latest/networking/XDP/implementation/xdp_actions.html

- https://toonk.io/building-an-xdp-express-data-path-based-bgp-peering-router/index.html

- https://duo.com/labs/tech-notes/writing-an-xdp-network-filter-with-ebpf

- https://github.com/xdp-project/xdp-tutorial/

- https://ebpf.io

- https://medium.com/@fntlnz/load-xdp-programs-using-the-ip-iproute2-command-502043898263

- https://www.winet.dcc.ufmg.br/ebpf/processamento_rapido_de_pacotes_com_ebpf_e_xdp.pdf

- https://qmonnet.github.io/whirl-offload/2016/09/01/dive-into-bpf/

- https://docs.cilium.io/en/v1.8/bpf/